In 1972, when I was 5 years old, my GP noticed some sort of murmur and referred me to a cardiologist, who diagnosed a mild stenosis of the aortic valve. Auscultation, chest x-rays, ECG and at last a heart catheter were used to further assess the condition at that early age. Whilst the condition was not considered critical, and I was asymptomatic, a 2-yearly monitoring cycle was recommended. I was a skinny, energetic and sporty child and played club tennis with regional competitions during teenage years. From age 13-22 annual reviews were undertaken, brought back again to a 2-yearly cycle until age 28. As I continued to be asymptomatic and every examination for decades had brought largely the same result “no progression of the mild aortic stenosis”, I decided not to worry about it any longer and had the condition only very sporadically assessed – at ages 33, 41, and 53.

The first Ultrasound examination done on me was in 1982, and this would then substitute every other x-ray examination (reducing exposure). It was not until 1999 (age 33), when apparently ultrasound resolutions were suitable to “presume” a bicuspid aortic valve (BAV) as the underlying condition for the aortic stenosis. For me this appeared to be a new name for the same thing, and nothing changed with regards to recommendations regarding my physical activity (ie no highly strenuous, competitive sports).

A link between BAV and a dilating ascending aorta was never suggested to me by any specialist. An ultrasound report from 2007 (aged 41) for the first time spoke of 4.7cm ascending aorta diameter; however, the consolidating/referring cardiologist’s report does not mention this finding in his report.

To this end I was more than surprised when my cardiologist in early 2020 (aged 53) suggested that I should seriously consider prophylactic surgery based on the then measurement of 5.1cm (diameter ascending aorta). Aortic root replacement and, while they’re at it, they can also do your valve. Why don’t you see the surgeon, he’ll be here tomorrow!?

My entire life I have been healthy, physically active and in particular entirely asymptomatic with regards to any heart issues. I grew up on the bicycle, have been hiking and jogging for enjoyment and to keep fit throughout my adult life. (Fair to say that since the age of 40 my level of general activity and with it my fitness has declined somewhat.) Owing to this background I did not want to “give in” to my cardiologist’s recommendation to consult a surgeon and ask for his opinion. (If you ask someone with a hammer what to do with a nail…). Instead, I undertook research trying to find support for my ‘do-nothing (yet)’ inclination. I did find some support in various international papers that estimate risk-probabilities for various groups of aortic aneurysm patients. However, it became clear that I was at best not far away from borderline, where most specialists would recommend that operating (aorta replacement) is of lower risk than not undertaking a procedure. Considering various indexing methods, I presumably had a 4-8%/yr probability for aortic rupture – a situation that would likely be fatal or at least very complicated.

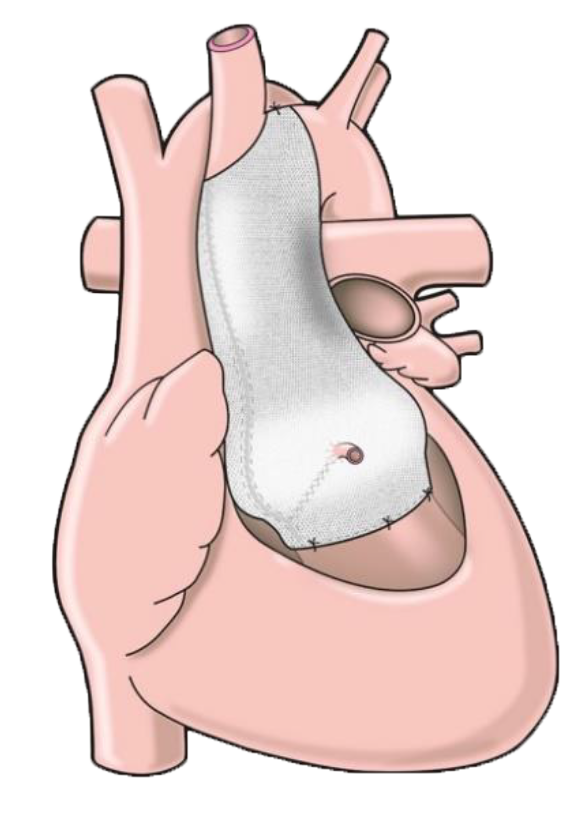

My cardiologist followed up with me to gently push for a decision, and explained to me the new PEARS procedure, that could be undertaken in Brisbane with the key surgeon being Dr Peter Tesar, a highly experienced heart surgeon. The potential advantages of the procedure compared to conventional aortic root replacement were obvious (likely no heart-lung machine, short procedure, no Warfarin later on), particular as I felt I might have good chances to leave the still very mild BAV insufficiency untouched – for now anyway.

Having my cardiac CT done at The Prince Charles Hospital and meeting with Dr Tesar in early October 2020 was a positive experience. I understood Dr Tesar to be one of the best surgeons in Australia to undertake PEARS. Sensing my ambivalence about whether to go down that path, he suggested that I should use the following two weeks to arrive at a decision for me personally, ie ‘What life do you want to live?’

I continued my research on aortic aneurysms, BAV, PEARS, discussed the situation with my wife, called my cardiologist again for a few remaining questions. At the end of the two weeks, I had my 54th birthday, and I stood fast, almost 100% determined that going ahead with PEARS asap was the way to go for me. I was then on the waitlist for elective PEARS procedure at The Prince Charles Hospital, a public hospital. The months of waiting were uncertain and somewhat daunting; however, they gave me a chance to internalise fully that I was doing the right thing for me and my family. All doubt had disappeared. The quiet support of my wife was invaluable during that process.

Summary of key reason for doing this elective surgery now

- The aneurysm is very likely to get worse. Risk of potentially severe or fatal rupture was real (whilst not extreme/immediate). My family needs me to be active and fit. I do not want to have any daunting physical limitation.

- The small (but growing) database of PEARS procedures suggest that it is very safe if the surgeons are experienced. (The limited base data of 317 PEARS patients in the latest study I found [Nemec/Pepper/Fila (2020) Personalised external aortic root support)] suggests fatal risk during operation of <1%; that compared to a 4-8% per year (!) risk (in my case) for aortic rupture appeared to be a very convincing argument.)

- The procedure is not open-heart and relatively short (2h). It does not per se require lifelong medication and no Warfarin.

- I am relatively young and healthy, have been a vegetarian for over 20 years, never smoked, never overweight, physically active, on no medication. Good chances that I would recover well from the procedure. Now is the best time to do it.

Admission

I was admitted to The Prince Charles Hospital on 2/2/21. However, in that week my procedure was cancelled 3 times due to unavailability of ICU beds. After all, I was no emergency case. Whilst this was a bit of a roller coaster and annoying for reasons of logistics, this trial week at least showed me how quickly fellow “inmates” got better, and that I was probably one of the healthier (and younger) people undergoing cardiac surgery, able to continue my little yoga and push-up routine at night. I even got a day-pass to leave the hospital during the day, and spend time with my wife walking through the woods, at times with a flickering dark question on my mind whether those would be my last walks… However, those were brief moments of doubt and I was generally in very positive spirits still convinced that I was doing the right thing for me.

I left the hospital again for the weekend, just to be re-admitted for take-two on Monday 8/2/21.

Day of procedure – Tuesday 9/2/21

By then I had met some 4 different anaesthetists, and generally knew the drill of shave, wash and Valium/O2. That day, however, I was actually picked up to go to the surgical theatre. Repeating my name/DOB back and confirming the procedure I was expecting (all part of the medical QA system), then the odd question as to on which side, right or left, the procedure was going to be carried out on. The last thing I remember was a confused “in the middle!”

I woke up again in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) in the evening of that day, my wife by my side and generally feeling fine. I realised that I was past the procedure, my wife told me that the doctors had said that all had gone according to plan, ie pure PEARS. I was told all about the lines and drips out of my body and taught how to adjust the level of pain medication (Fentanyl). Spent a night with one-on-one care in the ICU – couldn’t have been more perfect.

| Day 1 | In the morning, still in ICU two people mobilised me in a walking frame, with all my wired/hosed connections, noticed my drainage hose was somehow oozing on the floor. But not to worry, the hole was slightly bigger than the hose, nothing else. Then a mobile x-ray machine came along and took a pic of me, too. All very impressive. No appetite and feeling a bit sick, I was wheel-chaired to the ward less than 22h after I had arrived in the ICU. With three buddies in the room, I still felt a bit average and pushed my pain relief button somewhat regularly. Getting hungry yet feeling sickish. Not a great night, plenty of interruptions/measurement of obs data. |

| Day 2 | Got disconnected from Fentanyl. Physio walked a few steps with me (still connected to plenty of hoses and bits) and showed me all sorts of exercises. Spirometer lung training was hard work! In the evening, urinal catheter was disconnected with the only remaining line being the wound drainage. Sleeping was very poor due to back pain and noise in the room and from fellow patients. |

| Day 3 | Drainage was disconnected. Free at last! Went walkabout around the ward several times that day trying to re-activate body and gut. Physio: walking and arm exercises. Evening post-procedural ultrasound; I was a bit apprehensive as the pre-procedural one was rather painful (due to ribcage physique), however, it was not painful this time/looked for other bits (fluid pockets etc). |

| Day 4 | Physio: walking, stairs, pulse test – done! Good news from x-ray/ultrasound that there are no significant fluids left in lung/around heart. Walkabout beyond ward doors, down to café. Still poor appetite but trying to eat something. Had visitors in the evening and a long chat – which was a bit ‘breath-taking’. |

| Day 5 (Sunday) |

X-ray – zero fluid pockets. Still had temperature in the 37s, however, discharge from hospital was OK’d. Now on Paracetamol (pain), Aspirin (thinner) and Colchicine (inflammation). Picked up by family and driven home (2h) – home sweet home! How good is that! |

First week at home (Days 6-12)

Continued to measure and document my ops data (blood pressure, temperature) 4-5 time per day and took the medication as prescribed (Paracetamol, Aspirin, Colchicine). Slightly elevated temperature continued throughout the week measuring in the low to mid 37s (despite Panadol), some night sweats. Pushed myself on the unpleasant spirometer lung work-out (‘baby-steps towards success’). Blood pressure typically around 135/90 with a pulse of 85 – quite a bit higher than pre procedure (125/80, resting pulse of 59). Whilst my heart rate would go up noticeably when walking during the initial days at home, this improved and felt less stressed from day 9 onwards. Nights would typically be interrupted at least once with backpain being the main nuisance. Would take 1-2 day-naps. Increasing walking activity, typically twice a day to the nearby park. Quickly up to 4-5km/day. Overdid the walking a bit on day 11 with over 8km, which made me very tired that evening/night.

GP visit on day 10 (Fr). Heart rate and sound, blood pressure, wound and legs inspection – all good.

Day 14 (Tue 22/2) – I had been feeling my heart beat a lot since the procedure, feeling it everywhere, in the chest, the neck, the back, hearing it. But this was different: sitting down, my t-shirt would move in and out in crazy rhythms and rather fast. Went to GP, who did an ECG and diagnosed rapid atrial fibrillation (AF) – irregular beats up to 180 bpm in the atrium whilst the pulse was slower than normal. While this was happening, I had no pain nor any particular feeling of discomfort. Yet, the ambulance chauffeured me to the nearest hospital.

Monitoring, ECG, x-ray, intravenous saline solution to beef up my hydration. As nothing changed, I was given Amiodarone (K-blocker), and Metoprolol (ß-blocker), which brought my rhythm back within one hour. I stayed for 2 nights in hospital to be monitored. No relapse of the AF has happened (to date, day 42/6 wks post op). Coming home after this intermezzo my son had a serious cold (no covid). As a precaution I stayed for two nights at the in-law, which was terrific. Wouldn’t want to catch a cold in this phase; coughing and sneezing are really rather painful even with a strong cross-grip holding chest together.

This episode brought home to me that the healing process might not be quite as linear as I had begun to assume. Uncertainty! I realised that I might have been well informed about my conditions and the procedure itself, but not about what to expect in the weeks and months after. Only when I had AF, I was finally told that some 40% of open chest cardiac patients get it, one way or the other – hence, it should not have been a big surprise. Once I was connected to the PEARS Facebook group (“The Most Exclusive Club on the Planet”) sharing my AF experience, I heard left, right and centre that AF is a common experience.

Days 17-42 post procedure have been relatively smooth. Yes, the sternum healing needs patience and technique – lifting in the right way and you do need plenty of family support if you’re lucky enough to get it – but overall my healing trajectory has been pretty steep. My resting pulse has bit by bit come down from the mid 80s back down to the low 60s; let’s see when I get back to my old 59 bpm. Six weeks after my surgery I am glad I have gotten through this phase relatively easily, and that I decided to do it. I feel really well.

A word about the hospital and its magicians

The Prince Charles Hospital in Brisbane (TPCH) is a public hospital renowned for its cardio-thoracic expertise. During my initial “trial week” I got to know some of the nurses and doctors, the ‘wardies’/support staff, and the procedures related to my ward. Then after my procedure, when I really needed the support, I was nothing short of impressed by all staff. Realising how physically and mentally on edge one can get as a patient in this ward, I cannot but compliment in the highest all staff and the apparatus of TPCH. Apart from their professional know-how and experience, the softer personal skills seem to become so much more important in the medical and nursing profession. The Fingerspitzengefühl (‘fingertip sensitivity’), ie the knowing how to react, how to approach, how to best help a patient must be incredibly demanding and clearly goes beyond everything an engineer and commercial professional like me will ever need.

During my entire time at TPCH, I felt secure, looked after, cared for and provided with the highest level of medical treatment and support.

One last word of praise for the Australian public health insurance. Internationally it is not a given that both significant and new procedures like PEARS are being fully covered. It is absolutely remarkable that Medicare allows this and that top surgeons provide their services in public hospitals.